How Cyanotypes (and Charleston’s Female Artists) Preserve Fleeting Beauty

From early photography to the Charleston Renaissance—how women have preserved beauty and history.

There’s something magical about using the sun to create a photograph—an image shaped by light, time, and a little serendipity. My upcoming collection is all about capturing that magic through the timeless art of cyanotype printing.

A Bit of History

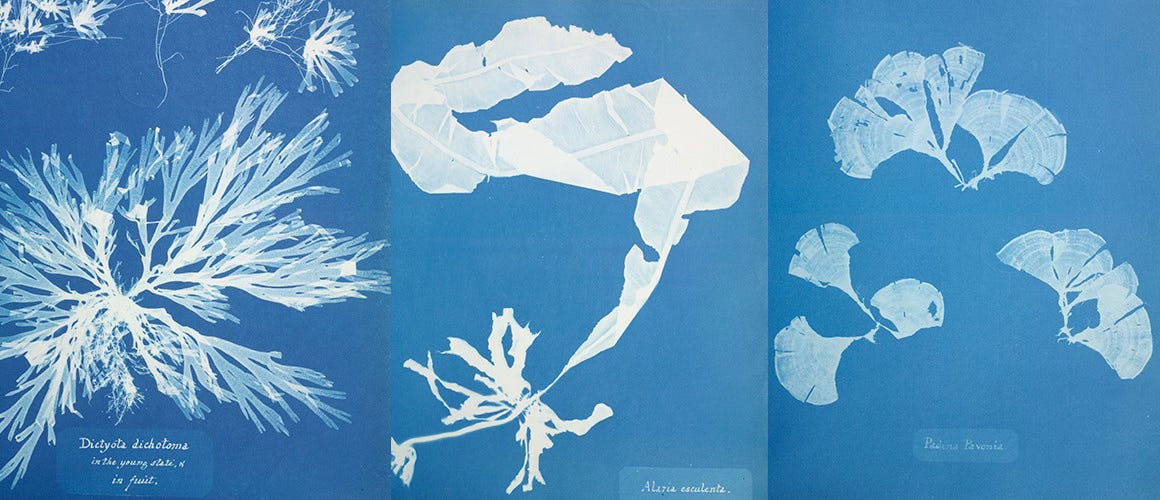

Cyanotype is one of the oldest forms of photographic printing, dating back to 1842 when English scientist Sir John Herschel developed it. Originally used for copying notes and blueprints, it took a botanist and photographer—Anna Atkins—to see its artistic potential. She created an incredible collection of cyanotype prints featuring algae and ferns, making her one of the first, if not the first, female photographers.

The process itself is simple but fascinating. You coat paper with a light-sensitive solution, let it dry in darkness, then expose it to sunlight. The result? Deep Prussian blue images, each one shaped by the elements in real time. (I shared more about the process in a post a couple of weeks ago.)

The Beauty of Handmade Prints

No two cyanotypes are exactly alike. The texture of the paper, the saturation of the chemicals, the strength of the sun, exposure time—even the humidity (talk to me in August)—all affect the final image. That mix of science and spontaneity is what makes each piece so special.

This collection will include both traditional cyanotypes and digital prints that have been carefully edited to recreate that rich, layered blue. Whether printed under the sun or refined digitally, each piece stays true to the spirit of this centuries-old technique.

Charleston, Cyanotypes, and the Women Who Captured a City

Charleston’s art scene has a certain magic—something I felt immediately when we moved here almost 15 years ago. There’s a deep appreciation for art, a commitment to both preserving and creating, and an incredibly supportive community of artists. Inspiration is everywhere. And while we often hear about the grand portraits and landscapes of the past, the real heartbeat of Charleston’s art history includes women who don’t always get the spotlight they deserve.

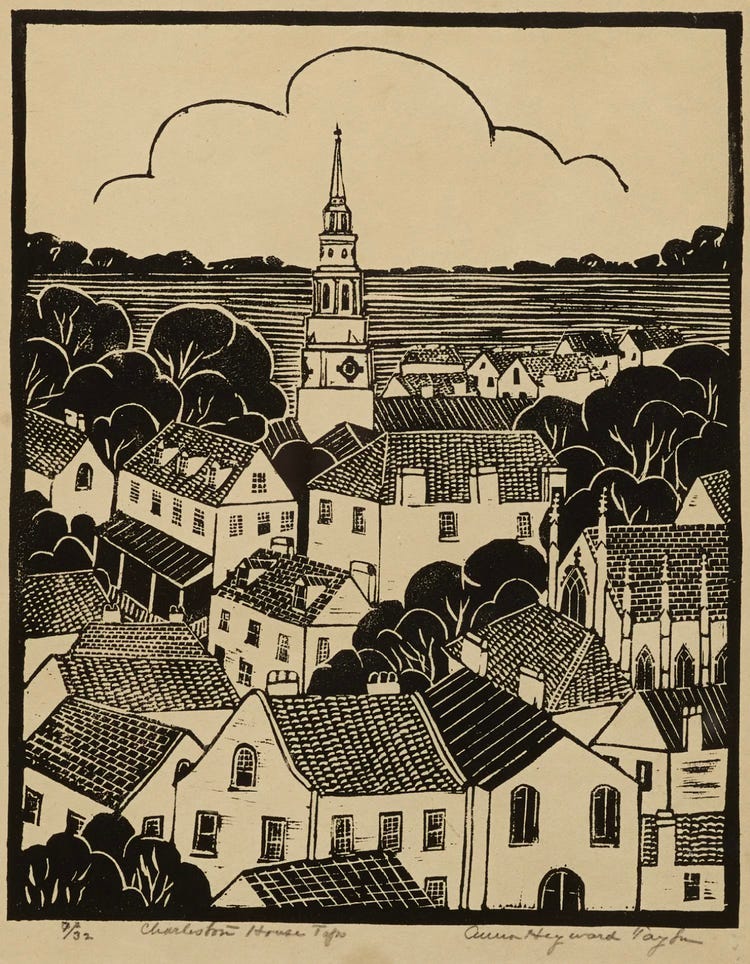

Between the World Wars, Charleston experienced an artistic revival that helped fuel the city’s tourism industry—something still very much alive today. At the center of it were three remarkable women: Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, Anna Heyward Taylor, and Elizabeth O’Neill Verner. Their work still shapes how we see Charleston. Smith’s watercolors captured the quiet beauty of the Lowcountry, Verner’s etchings and pastels documented everyday city life, and Taylor’s bold, layered prints—heavily influenced by her travels—brought new energy to Southern art. They weren’t just creating; they were preserving history, and in Verner’s case, even advocating for historic preservation before it was fashionable.

It makes me think of Anna Atkins, the cyanotype photographer I mentioned earlier—capturing something fleeting before it disappeared. In a way, that’s what Smith, Taylor, and Verner did for Charleston. Whether through paint, print, or photography, they froze moments in time, preserving the feeling of a place before it could fade.

And that’s what so many of Charleston’s female artists are still doing today. Their work carries on that same tradition—documenting, preserving, and reimagining a city that’s always changing but never loses its charm.

Do you have other questions about Charleston or cyanotypes? A favorite artist I should feature? Leave a comment!

Thanks for being here! I’d love your help sharing my work!

If you enjoyed this post, tap the ❤️ button so more people can find it. Subscribe to continue reading Highlightings, and even better—share it with friends who may be interested! (You earn rewards for every referral!)

For more, follow me on Instagram or visit www.pjmphoto.com.